800 tonnes of sawdust was recently turned into fuel pellets in a globally unique test run in Sweden. That was part of a pellet research project that is being carried out on a large scale to investigate differences in quality between different raw material compositions.

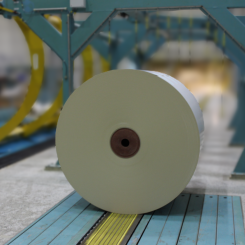

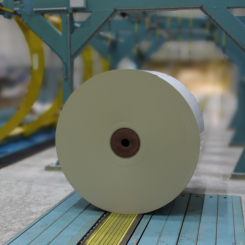

Fuel pellets are a cheap and environmentally friendly energy source made from dried and compacted sawdust from spruce and pine. Therefore, they are a valuable and important component in the transition to a fossil-free society.

In order to optimize the production and storage of pellets, a research study is now investigating whether the pellet quality is affected by the origin of the sawdust: the heartwood (coarse timber) or the sapwood (small timber).

What the researchers are investigating is whether the handling of the raw materials can contribute to making the pellets more resource-efficient. The method includes studying how low- and high-temperature drying, in combination with small and coarse timber, affects the physical properties and long-term storage.

One problem when storing fuel pellets is that they can generate spontaneous heating, forming flammable and toxic gases. The researchers aim to reduce this increased fire hazard.

In order to examine the improvement opportunities in the context of fuel pellets, some 800 tonnes of fresh small and coarse timber from pine was transported to the pellet plant of power company Härjeåns Energi in the Swedish town of Sveg. That is where the impressive test run took place.

“This is huge. Such large-scale research trials aren’t carried out anywhere else in the world. Normally, you’d go to a lab and do smaller runs,” says Magnus Persson, who is an innovation advisor and project manager at Paper Province.

What makes this volume possible is the collaboration between academia, research and industry.

“If this turns out well, it’s going to have an impact for the entire industry: everyone will be able to learn and benefit from it.”

The test run was the second of two major ones. The first one, completed last autumn, involved low-temperature drying. This time, however, a high-temperature dryer was used.

“The test run came out well, and now we’ll continue the measurements and analyses in order to determine the outcome,” says Michael Finell of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

He is the project manager for InnoPels, the project where the research is conducted. It is funded by Vinnova, with the participation of Karlstad University, Paper Province, Solör Bioenergi Pellets AB, Härjeåns Energi AB and Bergkvist Siljan Skog AB.